While Heartfelt, ‘Life, Animated’ Squanders Its Cinematic Potential

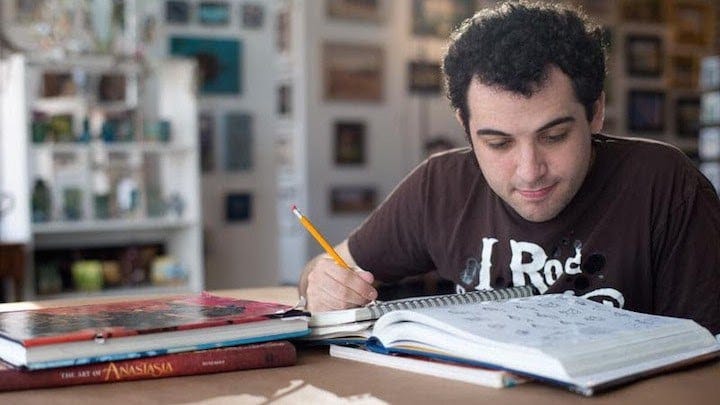

Owen Suskind was diagnosed with autism when he was three years old. Now he is 23, preparing to move into his own apartment. Once, in early childhood, his parents thought he might never speak again. After years of education and struggle, he is now entering the world. His story is as inspirational as it is important, a shining light in the fight to combat…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.