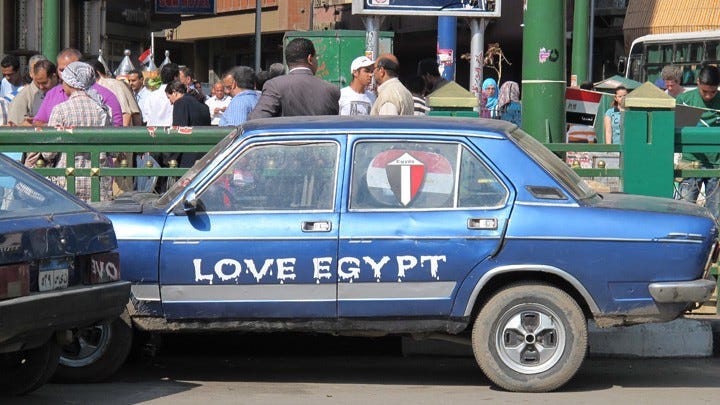

True/False 2014: ‘Cairo Drive’ Review

From above, Cairo looks like a city populated almost entirely by vehicles. Taxis, buses, tuk-tuks, motorbikes, microbuses and pedestrians all come together in enormous traffic jams. Getting around is a constant struggle, simultaneously a charming video game come to life and a troubling threat to the lives and livelihoods of many Egyptians. When you hear…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.