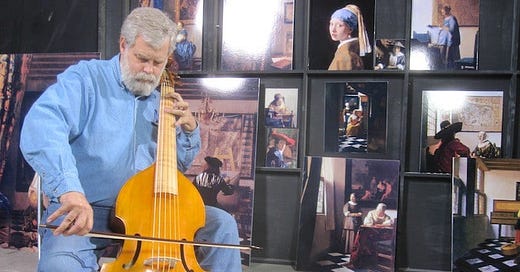

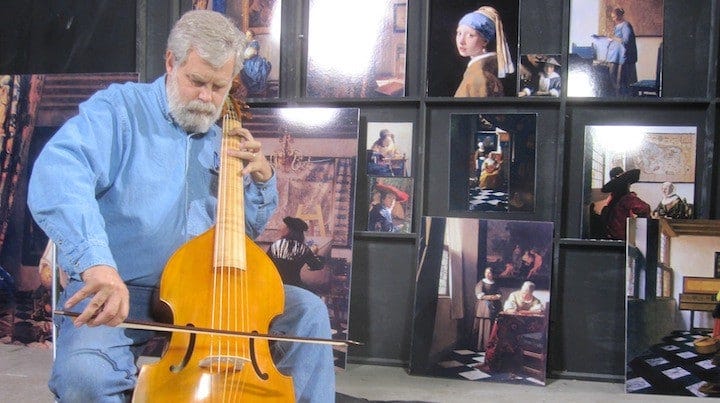

‘Tim’s Vermeer’ Subject Tim Jenison On How the Film Blows the Lid Off Art History

Tim Jenison is not your typical documentary subject, which is why I went against my usual rule and agreed to interview him. It may have been the first time I talked solely with a nonfiction character without also interviewing the filmmaker. Breaking another rule, I also agreed to the interview without having seen the film in question, Tim’s Vermeer, whi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.