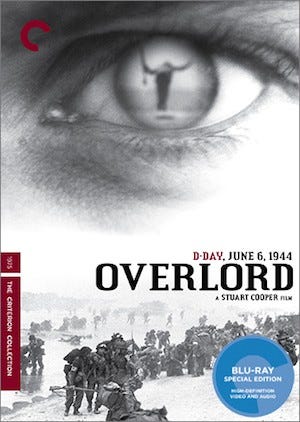

The Past is Ever Present: Stuart Cooper’s ‘Overlord’ and the Memory of War

The moving image has played an essential role in our public memory of WWII. From wartime newsreels to soldiers’ home movies to propaganda to visual records of concentration camps, WWII was saturated by an incredible archive of striking images from the outset, images that have helped shape our understanding of history and the way we continue to tell it. …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.