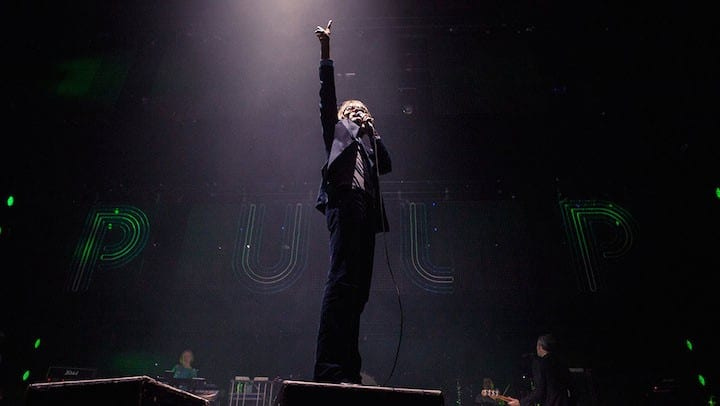

‘Pulp’ Review: A Rockumentary For the “Common People”

Written by Landon Palmer

British rock band Pulp’s best-known song, “Common People,” is a satire of cultural tourism, an indictment of the valorization of working-class authenticity by those who do not belong to it. As working-class identity has been an essential part of British rock ’n’ roll, “Common People” is essentially a middle finger to interloping posers, to those who hav…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.