Now On DVD: ‘We Come As Friends’ Is a Stunning Look At the New Imperialism In Africa

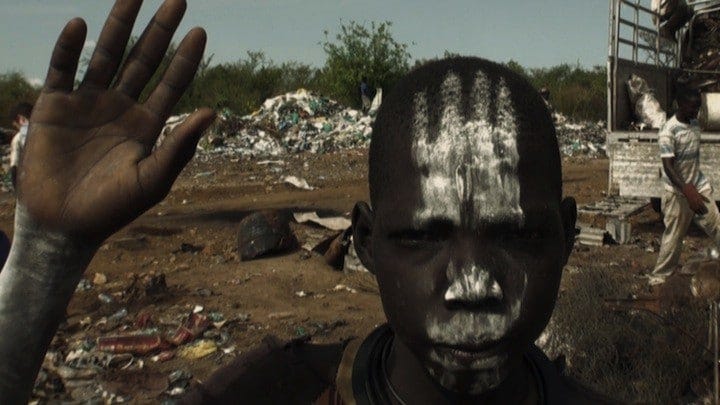

We Come As Friends sounds like the title of a science fiction film, not a documentary about contemporary Africa. Early on, a Sudanese storyteller narrates how the white man has claimed even the moon as his own. In this film’s worldview, the interlopers from rich nations are otherworldly invaders, far scarier than any alien foe Hollywood ever dreamed up.

…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.