Martin Scorsese’s ‘The 50-Year Argument’ is More Accessible Than You Think

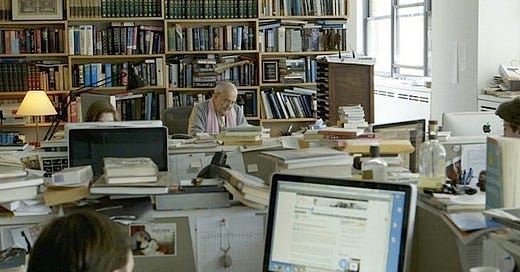

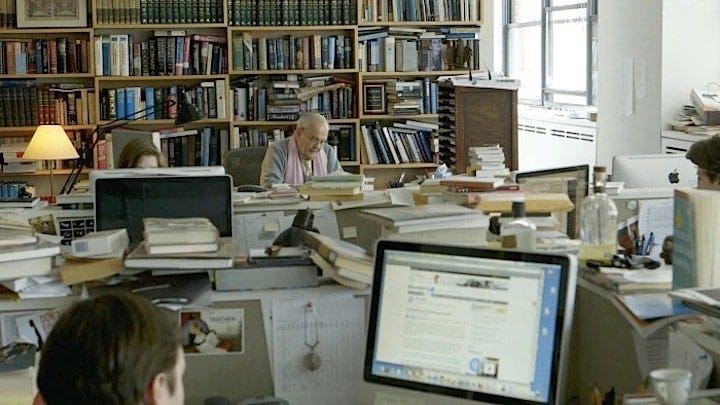

Following his films on cinema and his films on music artists, Martin Scorsese is now in a period of films on writers, whether that’s intentional or not. In addition to this year’s Life Itself, which he produced, there’s the 2010 Fran Lebowitz doc Public Speaking and now the New York Review of Books profile titled The 50 Year Argument.

What sounds like a …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.