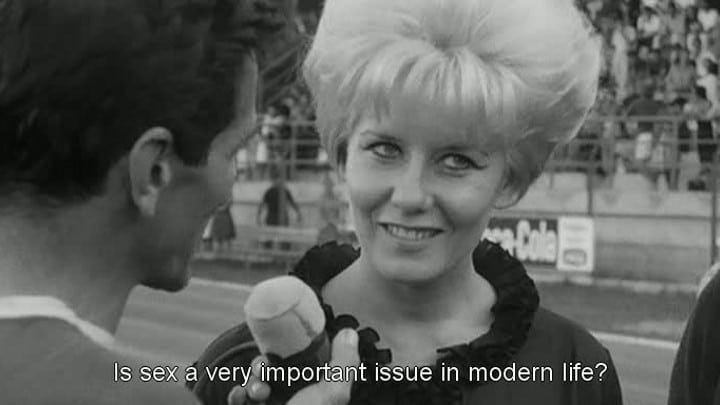

Let’s Talk About Sex: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘Love Meetings,’ 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago, Pier Paolo Pasolini turned to the public and asked them a series of uncomfortable questions. They took it surprisingly well. The resulting film, Love Meetings, had its world premiere on July 26, 1964, at the Locarno Film Festival. It’s essentially an informal Kinsey survey, in which Pasolini travels up and down the Mediterranean asking …