‘John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection’ is an Extraordinary Lie

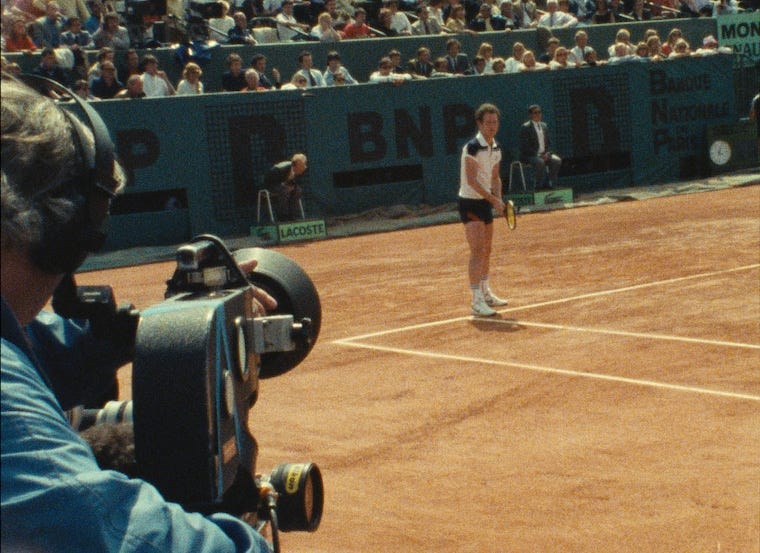

This is not a film about John McEnroe. And yet it is a film of John McEnroe. This is the sort of distinction that I tend to reserve for more experiential documentaries. The sort that follows a subject in their life or in its existing state rather than telling us about them. John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection does showcase the eponymous tennis play…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.