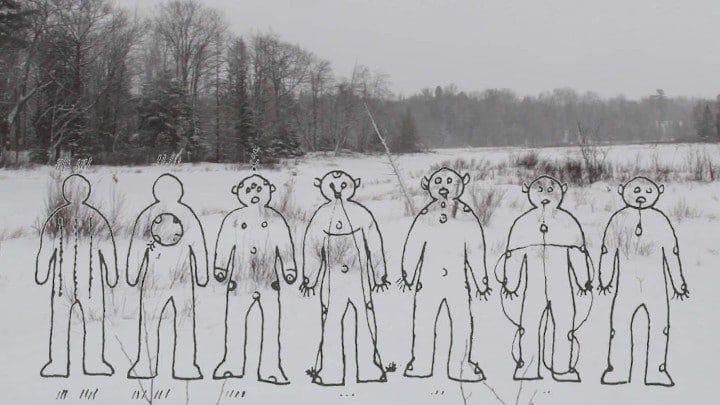

‘INAATE/SE/’ Is a Unique and Transformative Retelling of Native American History

Every one in a while, a film comes around that so bluntly and creatively rejects the dominant form of documentary expression, it feels like something brand new. INAATE/SE/, the debut feature by brothers Adam and Zack Khalil, is one of those revelations. Yet neither the story they tell nor the way they express it to the audience is entirely original. It …