‘Fire in the Blood’ Review

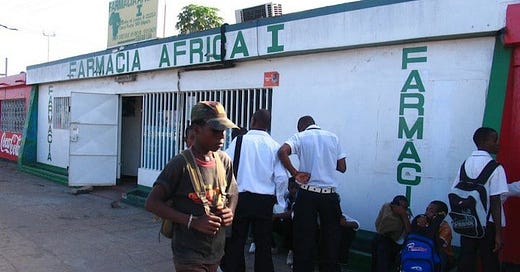

They say truth is stranger than fiction. It is also harsher. While watching Dylan Mohan Gray’s Fire in the Blood, about the AIDS crisis in Third World nations and the issue of Big Pharma just letting millions die by not availing them cheaper drugs, I couldn’t help but think of the recent sci-fi movie Elysium. That Hollywood blockbuster is about a dystop…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.