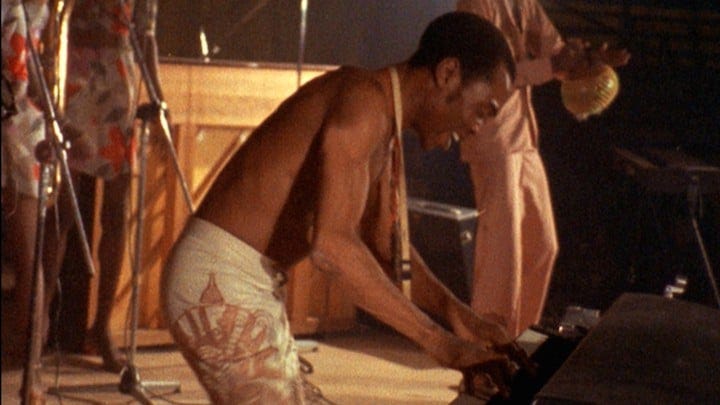

‘Finding Fela’ Review: A Muddled and Disappointing Biography of Fela Kuti

Written by Landon Palmer

Alex Gibney opens his documentary on Fela Kuti — the Nigerian musician and activist whose global renown as an African political dissident was said to be second only to Nelson Mandela — by examining the production of Fela!, the 2009 hit Broadway musical about Kuti. It’s a strange choice to make for a documentary that presents itself as an exhaustive exam…