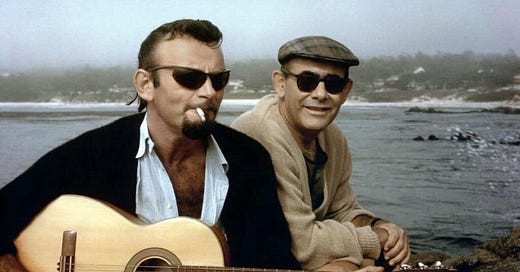

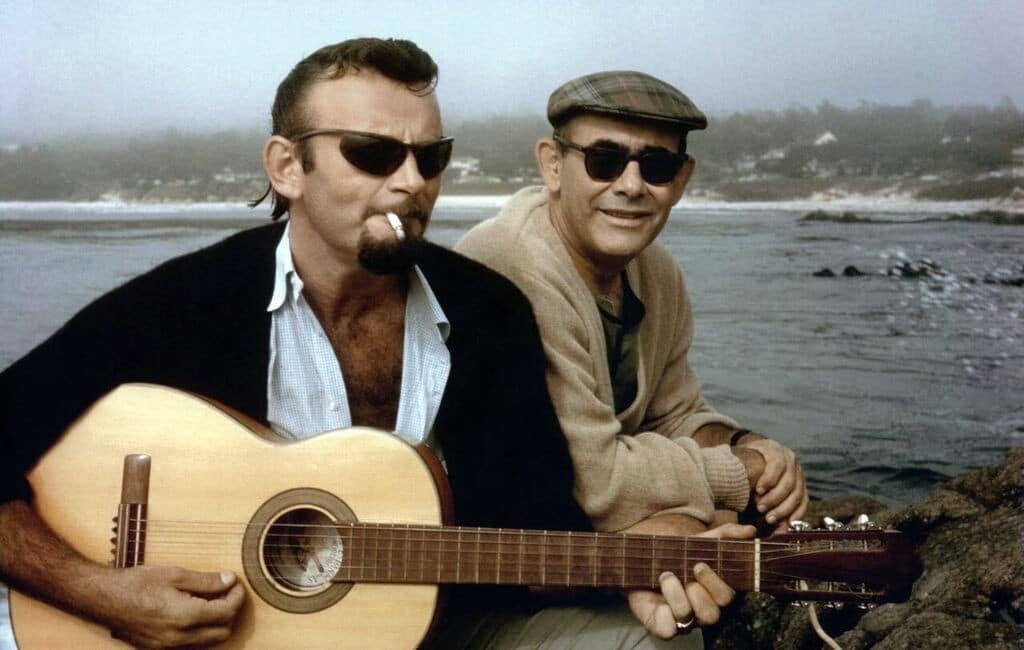

Behind the Music Making: ‘Bang! The Bert Berns Story’ Celebrates the Industry

A fun look at the man behind “Twist and Shout.”

“Back in the day, good records were made,” Betty Harris, singer of such songs as “Cry to Me,” tells us in the middle of Bang! The Bert Berns Story. The movie is a celebration of the writer of that particular ditty, a man named Bertrand Russell Berns, who hailed from the Jewish corners of the Bronx. In addit…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.