‘After Tiller’ Review

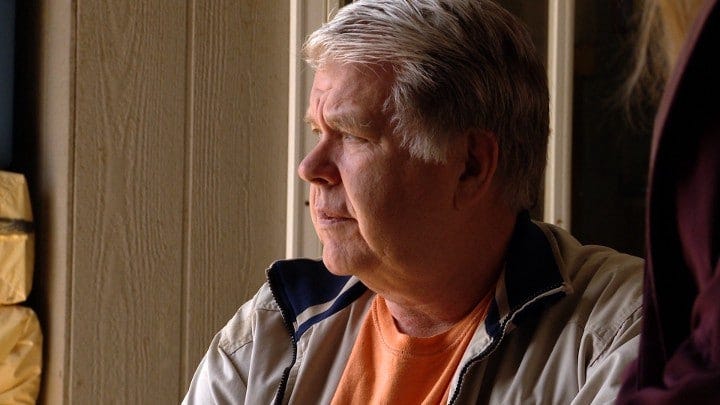

Dr. LeRoy Carhart is looking for a fight. He admits as much himself. He’s an abortion provider sick of being run out of town, tired of watching the anti-abortion movement achieve political victories. He was forced out of Nebraska when a law banning abortion after 20 weeks was passed, and when he tried to move his practice to Iowa, the town fought back. …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.